common name: zebra swallowtail

scientific name: Protographium marcellus (Cramer) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Papilionidae)

Introduction - Synonymy - Distribution - Description - Life Cycle - Natural Enemies - Hosts - Selected References

Introduction (Back to Top)

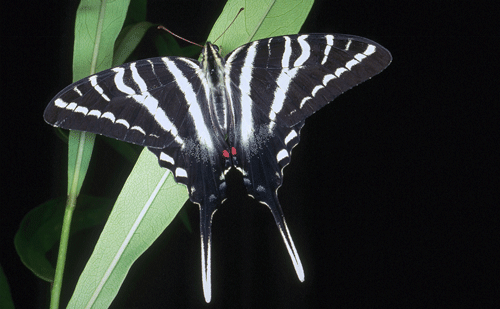

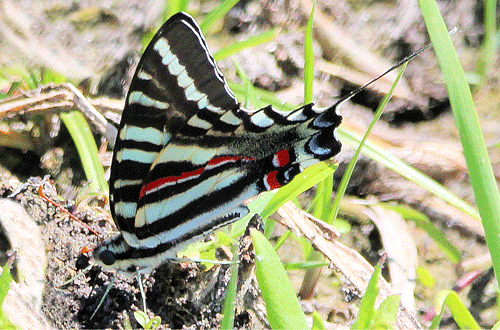

The zebra swallowtail, Protographium marcellus (Cramer), is our only native U.S. kite swallowtail (tribe Leptocircini [=Graphiini]) (Opler and Krizek 1984). It is one of our most beautiful swallowtails (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1. Zebra swallowtail, Protographium marcellus (Cramer), with wings spread. Photograph by Jerry F. Butler, University of Florida.

Figure 2. Zebra swallowtail, Protographium marcellus (Cramer), with wings closed. Photograph by Donald W. Hall, University of Florida.

Synonymy (Back to Top)

The zebra swallowtail was originally grouped with the other butterflies in the genus Papilio and named Papilio ajax by Linnaeus (1758). It has also been placed in the following genera:

- Iphiclides Hübner

- Graphium Scopoli

- Protesilaus Swainson

- Cosmodesmus Haase

- Eurytides Hübner

- Neographium Möhn

- Protographium Munroe

For many years the zebra swallowtail was known by the genus name Eurytides until Möhn (2002) moved it from Eurytides to the genus Neographium and most recently, Lamas (2004) moved it to the genus Protographium. The name Protographium is now being used in recent taxonomic journal papers (e.g., Allio et al. 2020, Condamine et al. 2018), but Eurytides is still used by some field guides and butterfly books (e.g., Evans 2008, Glassberg 2017).

Distribution (Back to Top)

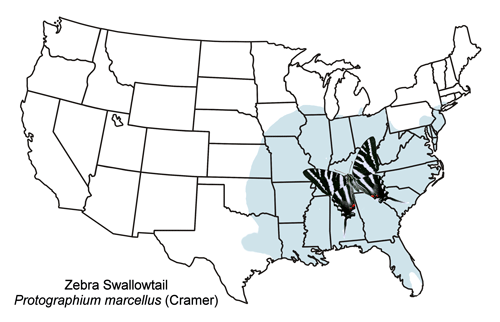

The zebra swallowtail is widely distributed from southern New England west to eastern Kansas and south to Texas and Florida (Figure 3).

Figure 3. General distribution map for the zebra swallowtail, Protographium marcellus (Cramer).

Description (Back to Top)

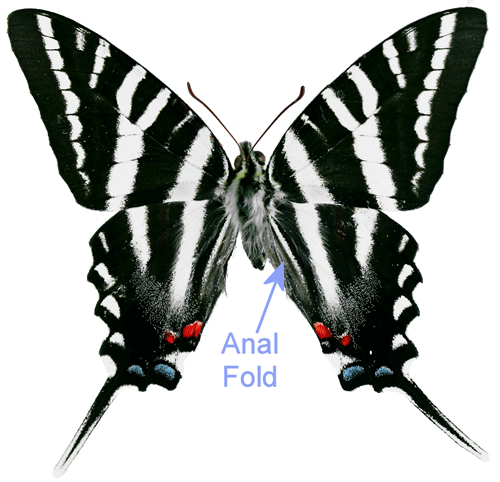

Adults: The wingspread of adults is 2.5 to 4 inches (64 to 104 mm) (Opler and Malikul 1992). The upper surface of the wings is white with black stripes. The hindwings have very long tails. The lower surface of the wings is similar except there is a red stripe running through the middle of the hind wing. Zebra swallowtails exhibit seasonal polymorphism. Early spring specimens are lighter in color, smaller, and have shorter tails (Scott 1986). There are also transitional forms. Mather (1970) detailed descriptions of the color forms. For lists of the names that have been used for the seasonal and transitional forms, see Tyler et al. (1994) or Heppner (2007). Unlike most of our other native swallowtails, zebra swallowtails are not involved in a mimicry complex. Males have a patch of elongated sex pheromone producing scent scales (androconia) in the anal folds (Figure 4) of the hind wings (Scott 1986, Simonsen et al. 2012).

Figure 4. Male zebra swallowtail, Protographium marcellus (Cramer) showing anal fold. Photograph by Donald W. Hall, University of Florida.

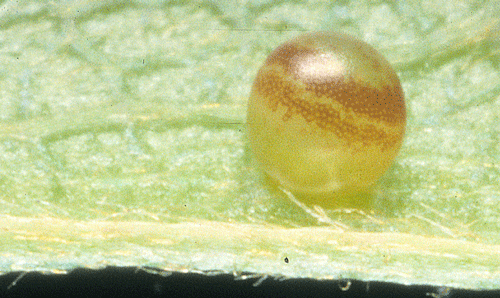

Eggs: Eggs are pale green (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Egg of zebra swallowtail, Protographium marcellus (Cramer). Photograph by Jerry F. Butler, University of Florida.

Larvae: For detailed descriptions of the larval instars, see Edwards (1862-1897) and Scudder (1889). Early instar larvae (first and second instars) are dull gray (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Early instar larva of Protographium marcellus (Cramer). Photograph by Donald W. Hall, University of Florida.

Middle instar larvae (Figure 7) are dark colored with transverse black, yellow, and white bands.

Figure 7. Middle instar larva of Protographium marcellus (Cramer). Photograph by Donald W. Hall, University of Florida.

Fifth (last) instar larvae (Figure 8) are green with broad blue, black, and yellow transverse bands between the thorax and abdomen and usually yellow bands between abdominal segments and numerous fine transverse black lines on thorax and abdomen. However, larvae exhibit color polymorphism, and some fifth instars are dark colored. The osmeterium is yellow (Figure 9).

Figure 8. Last instar larva of zebra swallowtail, Protographium marcellus (Cramer). Photograph by Donald W. Hall, University of Florida.

Figure 9. Last instar larva of zebra swallowtail, Protographium marcellus (Cramer), with osmeterium extruded. Photograph by Donald W. Hall, University of Florida

Pupae: Pupae are dimorphic (green or brown) with light lines simulating a leaf-like texture and are supported with a silken girdle (Figures 10 and 11).

Figure 10. Green pupa of the zebra swallowtail, Protographium marcellus (Cramer). Photograph by Jerry F. Butler, University of Florida.

Figure 11. Brown pupa of the zebra swallowtail, Protographium marcellus (Cramer). Photograph by Donald W. Hall, University of Florida.

Life Cycle (Back to Top)

There are two flights in the North and many flights in Florida from March to December. Males patrol for females in the vicinity of host plants, and females frequently may be observed ovipositing on host foliage. Adults seek nectar at a variety of flowers, but the adult proboscis is shorter than those of other swallowtails. Therefore, zebra swallowtails cannot reach the nectar of long tubular flowers (Opler and Krizek 1984). Male swallowtails also obtain moisture and minerals (primarily sodium) from mud, a behavior known as “puddling” (Figure 12) (Cech and Tudor 2005, Minno and Minno 1999, Otis et al. 2006). While puddling is primarily a behavior of males, females have also been observed puddling (Berger and Lederhouse 1985).

Figure 12. Male zebra swallowtail, Protographium marcellus (Cramer), feeding at moist sand for moisture and minerals. Photograph by Donald W. Hall, University of Florida.

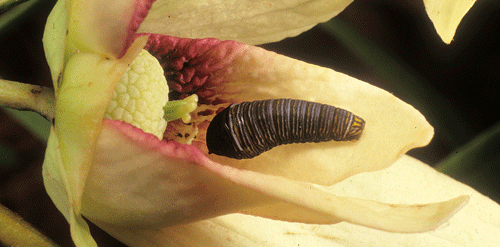

Females select young plants or plants with young leaves for oviposition (Damman and Feeny 1988). They respond strongly to host volatiles (as yet unidentified) that enhance landing rates and are then stimulated to oviposit by the contact oviposition stimulant 3-caffeoyl-muco-quinic acid (Haribal and Feeny 1998). Eggs are laid singly near the tips of young leaves (Wagner 2005) on which larvae prefer to feed. Larvae will also feed on flowers when available (Damman and Feeny 1988) (Figure 13). Larvae are highly cannibalistic (Klots 1951, Minno and Minno 1999, Wagner 2005).

Figure 13. Young larva of zebra swallowtail, Protographium marcellus (Cramer), in slimleaf pawpaw, Asimina angustifolia Raf., flower. Photograph by Jerry F. Butler, University of Florida.

The requirement for new leaves may limit reproduction of Protographium marcellus in summer and fall: however, production of new leaves during this period is often stimulated by defoliation of the host plant by larvae of the pyralid moth, Omphalocera munroei Martin (Figures 14 and 15) (Damman 1989). Therefore, late season abundance of Protographium marcellus may be dependent on the abundance of Omphalocera munroei. Omphalocera munroei larvae live in nests constructed by silking leaves together (Figure 16). The nests sometimes extend down stems as tubular structures. The outer layers of the silk nests are covered with frass (fecal pellets) (Figure 15) that may repel potential predators.

Figure 14. Omphalocera munroei Martin (Pyralidae) full-grown larva removed from nest. Photograph by Donald W. Hall, University of Florida.

Figure 15. Larval nest of Omphalocera munroei Martin (Pyralidae) covered with frass (fecal pellets). Note growth of new foliage stimulated by Omphalocera munroei defoliation. Photograph by Donald W. Hall, University of Florida.

Full-grown larvae evacuate the gut and begin to wander in search of a pupation site around mid-day (West and Hazel 1985). Larvae usually pupate on the under sides of either living or dead leaves of the host plant. Pupae formed on living leaves are usually green while those formed on dead (brown) leaves are usually brown (West and Hazel 1985, West and Hazel 1996). The brown pupa in Figure 11 resulted from a larva that was placed in a container containing only dead leaves and brown twigs immediately after it voided the gut and began to wander. Short photoperiod produces diapausing pupae that hibernate (Hazel and West 1983). However, some pupae of each flight overwinter (Scott 1986). Diapausing pupae are usually brown (Scott 1986) and are camouflaged on the dead leaves during the winter.

Natural Enemies and Defenses (Back to Top)

Zebra swallowtail eggs are occasionally parasitized by Trichogramma (Trichogrammatidae) wasps (Sime 2005). Larvae are parasitized by tachinid flies (Sime 2005) and the ichneumonid wasps Itopletis conquisitor Say and Trogus pennator (Fabricius) (Krombein et al. 1979).

The larval osmeterium (Figure 9) is coated with the strongly smelling chemicals isobutyric and 2-methyl butyric acids (Eisner et al. 1970). When disturbed, larvae extrude the osmeterium and smear the offender with the chemicals. At the same time the osmeterium is extruded, larvae regurgitate gut fluids. These fluids may become mixed with the osmeterial fluids, and Eisner et al. (2005) suggested that the effectiveness of the mixture may be enhanced by toxic compounds from the host plant contained in the regurgitated fluids. The larval host plants contain toxic acetogenins that would certainly be contained in the regurgitated fluids and are also sequestered by larvae and persist in the tissues and wings of adults (Martin et al. 1999). Some of these acetogenins have insecticidal activity against some insects (McGlaughlin 2008). It is unknown whether they offer any protection against parasitoids.

Osmeterial fluids have been shown to be an effective defense against small ants and spiders but not against most other predators or against the ichneumonid parasitoid of papilionids, Trogus pennator (Fabricius), which does not trigger extrusion of the osmeterium with its attacks (Damman 1986).

Larvae may thrash (Cech and Tudor 2005) or drop off the host plant when disturbed by a predator (Damman 1986). Older larvae sometimes hide in leaf litter at the base of the plant when not feeding (Damman 1986, Minno et al. 2005). The resemblance of the pupae to leaves provides protection from predators (Eisner et al. 2005).

Hosts (Back to Top)

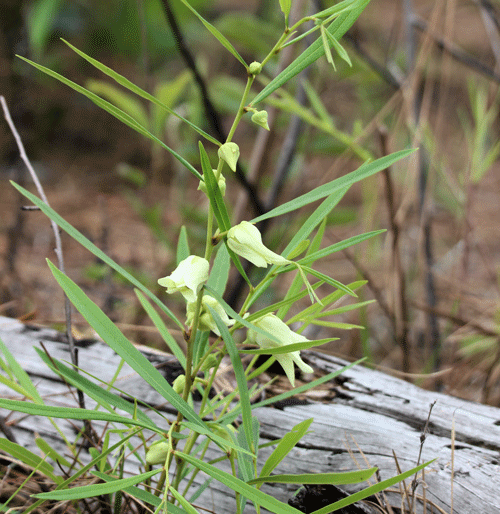

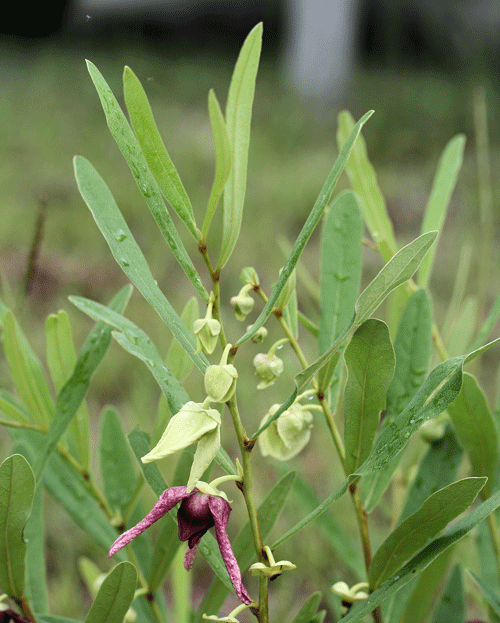

The larval host plants are Asimina species (pawpaws) (Annonaceae). Throughout most of the range of the zebra swallowtail common pawpaw, Asimina triloba (L.) Dunal (Figure 16), is the only host. In the deep South, other Asimina species are utilized (Minno et al. 2005) including smallflower pawpaw, Asimina parviflora (Michx.) Dunal (Figure 17), slimleaf pawpaw, Asimina angustifolia Raf. (Figure 18), woolly pawpaw, Asimina incana (W. Bartram) Exell (Figure 19), dwarf pawpaw, Asimina pygmea (W. Bartram) Dunal (Figure 20), fourpetal pawpaw, Asimina tetramera Small, netted pawpaw, Asimina reticulata Shuttlew. ex Chapm., pretty false pawpaw, Asimina pulchella (Small) Rehder and Dayton, and Rugel’s false pawpaw, Asimina rugelii B.L. Rob. Plant names are from Wunderlin et al. (2019).

Figure 16. Common pawpaw, Asimina triloba (L.)Dunal (Annonaceae), a larval host for the zebra swallowtail, Protographium marcellus (Cramer). Photograph by Donald W. Hall, University of Florida.

Figure 17. Smallflower pawpaw, Asimina parviflora (Michx.)Dunal (Annonaceae), a larval host for the zebra swallowtail, Protographium marcellus (Cramer). Photograph by Donald W. Hall, University of Florida.

Figure 18. Slimleaf pawpaw, Asimina angustifolia Raf. (Annonaceae), a larval host for the zebra swallowtail, Protographium marcellus (Cramer). Photograph by Donald W. Hall, University of Florida.

Figure 19. Woolly pawpaw, Asimina incana (W. Bartram) Exell (Annonaceae), a larval host for the zebra swallowtail, Protographium marcellus (Cramer). Photograph by Donald W. Hall, University of Florida.

Figure 20. Dwarf pawpaw, Asimina pygmea (W.Bartram) Dunal (Annonaceae), a larval host for the zebra swallowtail, Protographium marcellus (Cramer). Photograph by Donald W. Hall, University of Florida.

Selected References (Back to Top)

- Allio R, Scornavacca C, Nabholz B, Clamens A, Sperling FAH, Condamine F. 2020. Whole genome shotgun phylogenomics resolves the pattern and timing of swallowtail butterfly evolution. Systematic Biology 69(1): 38-60.

- Berger TA, Lederhouse RC. 1985. Puddling by single male and female tiger swallowtails, Papilio glaucus L. (Papilionidae). Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 39: 339-340.

- Cech R, Tudor G. 2005. Butterflies of the East Coast. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. 345 pp.

- Condamine FL, Nabholz B, Clamens AL, Dupuis JR, Sperling FAH. 2018. Mitochondrial phylogenomics, the origin of swallowtail butterflies, and the impact of the number of clocks in Bayesian molecular dating. Systematic Entomology 43(3): 460-480.

- Cramer P. 1777. De Uitlandsche Kapellen voorkomende in de drie Waereld-deelen Asia, Africa en America [Papillons Exotiques des Trois Parties du Monde l’Asie, l’Afrique et l’Amerique]. Amsterdam, Netherlands. Vol. 2. 152 pp.

- Damman H. 1989. Facilitative interactions between two lepidopteran herbivores of Asimina. Oecologia 78: 214-219.

- Damman H. 1986. The osmeterial glands of the swallowtail butterfly Eurytides marcellus as a defense against natural enemies. Ecological Entomology 11: 261-265.

- Damman H, Feeny P. 1988. Mechanisms and consequences of selective oviposition by the zebra swallowtail butterfly. Animal Behaviour 36: 563-573.

- Edwards WH. 1862-1897. The Butterflies of North America. Houghton Mifflin. Boston, Massachusetts. 3 vol.

- Eisner T, Eisner M, Siegler M. 2005. Chapter 64. Class Insecta, Order Lepidoptera, Family Papilionidae, Eurytides marcellus, the zebra swallowtail butterfly. pp. 297-303. In: Secret Weapons: Defenses of Insects, Spiders, Scorpions, and Other Many-legged Creatures. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts. 372 pp.

- Eisner T, Pliske TE, Ikeda M, Owen DF, Vásquez L, Pérez HP, Franclemont JG, Meinwold J. 1970. Defense mechanisms of arthropods. XXVII. Osmeterial secretions of papilionid caterpillars (Baronia, Papilio, Eurytides). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 63: 914-915.

- Evans AV. 2008. National Wildlife Federation Field Guide to Insects and Spiders of North America. Sterling Publishing. New York, New York. 497 pp.

- Glassberg J. 2017. A Swift Guide to Butterflies of North America. 2nd ed. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. 420 pp.

- Hazel WN, West DA. 1983. The effect of larval photoperiod on pupal colour and diapause in swallowtail butterflies. Ecological Entomology 8: 37-42.

- Haribal M, Feeny P. 1998. Oviposition stimulant for the zebra swallowtail, Eurytides marcellus from the foliage of pawpaw, Asimina triloba. Chemoecology 8:99-110.

- Hemming F (ed.). 1954. Opinions and declarations rendered by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. Opinion 286. International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature. 8(3): 29-48.

- Heppner JB. 2007. Lepidoptera of Florida. Part 1. Introduction and Catalog. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. Division of Plant Industry. (Volume 17 of Arthropods of Florida and Neighboring Land Areas). Gainesville, Florida. 670 pp. (7th [corrected] printing)

- Klots AB. 1951. A Field Guide to Butterflies of North America, East of the Great Plains. Houghton Miflin. Boston, Massachusetts. 349 pp.

- Krombein KV, Hurd PD Jr., Smith DR, Burks BD. 1979. Catalog of Hymenoptera in America North of Mexico. Volume 1. Symphyta and Apocrita (Parasitica). Smithsonian Institution Press. Washington, D.C. 1198 pp.

- Lamas GRG, Robbins RG, Field WD. 2004. Atlas of Neotropical Lepidoptera. Checklist: Part 4A. Hesperoidea - Papilionoidea. In: J. B. Heppner (ed.) Atlas of Neotropical Lepidoptera Scientific Publishers, Gainesville, Florida, 439 pp.

- Linnaeus C. 1758. Systema Naturae. Edition 10, volume 1. Holmiae, Sweden. 824 pp.

- Martin JM, Madigosky SR, Gu Z, Zhou D, Wu J, McLaughlin JL. 1999. Chemical defense in the zebra swallowtail butterfly, Eurytides marcellus, involving annonaceous acetogenins. Journal of Natural Products 62(1): 2-4.

- Mather B. 1970. Variation of Graphium marcellus in Mississippi (Papilionidae). Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 24: 176-189.

- McGlaughlin JL. 2008. Paw paw and cancer: Annonaceous acetogenins from discovery to commercial products. Journal of National Products 71: 1311-1321.

- Miller JY. 1992. The Common Names of North American Butterflies. Smithsonian Institution Press. Washington, D.C.

- Minno MC, Minno M. 1999. Florida Butterfly Gardening. University Press of Florida. Gainesville, Florida. 210 pp.

- Minno MC, Butler JF, Hall DW. 2005. Florida Butterfly Caterpillars and Their Host Plants. University Press of Florida. Gainesville, Florida. 341 pp.

- Möhn E. 2002. Butterflies of the World: Papilionidae 8: Baronia, Euryades, Protographium, Neographium, Eurytides. Part 14. pp. 1-12.

- Opler PA, Krizek GO. 1984. Butterflies East of the Great Plains. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, MD. 294 pp.

- Opler PA, Malikul V. 1992. A Field Guide to Eastern Butterflies (Peterson Field Guide Series). Houghton Mifflin Company. New York, N.Y. 486 pp.

- Otis GW, Locke B, McKenzie NG, Cheung D, MacLeod E, Careless P, Kwoon A. 2006. Local enhancement in mud-puddling swallowtail butterflies (Battus philenor and Papilio glaucus). Journal of Insect Behavior 19(6): 685-698.

- Rothschild LW, Jordan K. 1906. A revision of the American Papilios. Novitates Zoologicae 13(3): 411-752.

- Scott JA. 1986. The Butterflies of North America. Stanford University Press. Stanford, CA.

- Scudder SH. 1889. The Butterflies of the Eastern United States and Canada with Special Reference to New England. Vol. 2. Lycaenidae, Papilionidae, Hesperiidae. pp. 767-1774.

- Sime KR. 2005. The natural history of the parasitic wasp Trogus pennator (Hymenoptera: Ichneumonidae): host-finding behavior and a possible host countermeasure. Journal of Natural History 39(17): 1367-1380.

- Simonsen TJ, de Jong R, Heikkilä M, Kaila L. 2012. Butterfly morphology in a molecular age – does it still matter in butterfly systematics? Arthropod Structure & Development 41: 307-322.

- Tyler H, Brown KS Jr, Wilson K. 1994. Swallowtail Butterflies of the Americas. Scientific Publishers, Inc. Gainesville, FL.

- Wagner DL. 2005. Caterpillars of Eastern North America. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey. 512 pp.

- West DA, Hazel WN. 1985. Pupal colour dimorphism in swallowtail butterflies: timing of sensitive period and environmental control. Physiological Entomology 10(1): 113-119.

- West DA, Hazel WN. 1996. Natural pupation sites of three North American swallowtail butterflies: Eurytides marcellus (Cramer), Papilio cresphontes Cramer, and P. troilus L. (Papilionidae). Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 50: 297-302.

- Wunderlin, RP, Hansen BF, Franck AR, Essig FB. 2019. Atlas of Florida Plants. Institute for Systematic Botany, University of South Florida, Tampa, Florida. (http://florida.plantatlas.usf.edu) (Accessed April 23, 2020)